Participatory research and community engagement in climate and health research

Article

Article

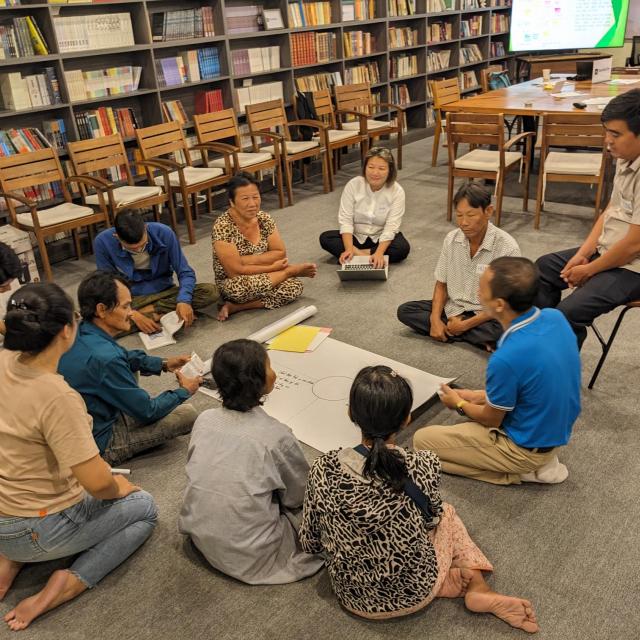

Photo from some of the co-construction activities involved in this project.

Anh Vu

In the wake of COP30 in Belém, global attention turns once again to the mounting health impacts of climate change. The World Health Organization’s recent Special Report on Social Participation in Health and Climate makes a clear and timely call: climate–health governance must move beyond expert-driven models toward participatory systems that centre the knowledge, agency and leadership of communities most affected by climate stress and health inequalities.

The WHO report positions participation not as an accessory but as a transformative force for climate justice and health equity. It aligns closely with the principles of the Belém Health Action Plan which highlights democratic dialogue, shared power, and the integration of local and traditional knowledge systems into climate–health policymaking.

Yet a critical question remains: what does genuine participation look like in practice—especially for those most exposed to climate-related health risks and least protected by formal systems? And how can it be operationalised in climate adaptation strategies?

This commentary responds to that challenge. Drawing on our Wellcome-funded, co-constructed research across four Vietnamese major cities (Hanoi, Da Nang, Ho Chi Minh City and Can Tho), it examines how informal outdoor workers – street vendors, porters, construction workers, and motor-bike taxi riders – experience and mitigate climate-related health risks. More than a study of vulnerability, it offers a practice-grounded account of meaningful participation in climate–health knowledge production, showing how everyday health risks and adaptation, embodied knowledge, and collaborative inquiry can inform more just and effective climate-health governance.

We worked with informal outdoor workers as co-researchers across all stages of the research – from design and fieldwork to analysis, authorship and policy engagement. This embedded collaboration not only surfaces the limitations of prevailing technocratic and biomedical adaptation frameworks, but also offers a grounded case for reorientating climate-health policy around lived expertise, structural constraints, and context-specific forms of resilience.

Our approach draws on the principles of co-construction—a method that centres epistemic justice and redistributes authority over the production and interpretation of knowledge. Arguably, co-production becomes meaningful only when it disrupts dominant power structures and interrogates who defines the problem, whose knowledge counts, and who benefits from decisions. A puzzle is that these principles have been central to critical development research and practice at least since Robert Chambers’ Rural development: putting the last first was published in 1983. And yet the challenge persists. In our research, this meant embedding workers not as passive participants but as active collaborators. They guided research questions, led ethnographic fieldwork, co-analysed findings, and reviewed the final outputs.

In our study, co-construction was not a methodological label but a sustained, embedded practice. It unfolded across four iterative phases with the workers:

This engagement – lasting between four and eight hours – enabled researchers to build relationships, observe work routines, and situate research questions within the everyday realities of informal labour. Following the first-round survey, in-depth interviews were conducted with a subset of participants to explore emergent themes in greater depth and maintain alignment between qualitative and quantitative strands of the study deepen thematic exploration.

Crucially, informal workers were not treated as informants but as co-researchers. From the outset, they contributed to shaping research priorities, co-designing and testing survey instruments, validating findings, and co-authoring outputs. In one instance, a street vendor’s feedback on how childcare responsibilities intersected with work routines under heat stress, prompting us to reframe several survey items to reflect these interdependencies.

This participatory ethos – centred on respect, reciprocity, and co-ownership – extended beyond data collection. Workers also collaborated in the development of the GIS-enabled mobile app – the Intelligent Climate Alert Network (ICAN) – designed to alert workers to localised weather-related health risks. They helped identify critical features, tested early prototypes, and provided feedback that directly shaped functionality. Many have since become regular users of the app – introducing it to their peers and networks – illustrating a non-extractive approach where knowledge co-production results in practical tools that continue to serve frontline communities.

Our co-constructed research with informal outdoor workers revealed three critical insights that challenge dominant climate-health frameworks. First, these workers possess a form of embodied environmental literacy: their understanding of weather shifts is grounded not in abstract climate data – meteorological fog – but in years of sensory engagement with extreme heat, rainfall, and pollution. As one lottery seller explained, “I can feel it right in my chest when the humidity’s too high—it’s not something a machine has to tell me” (INT12, Hanoi). Workers adapt their clothing, hydration routines, and even sales strategies in response to these microclimatic cues. Second, adaptation is inherently collective. Peer networks function as informal infrastructures of resilience—exchanging tips, providing emotional support, and collectively assessing risk. One participant noted, “When someone in our group feels faint, we all slow down. We take turns helping each other... it’s not just one person’s problem” (Focus Group, Ho Chi Minh City). These networks act as micro-level early warning systems and collective support systems and play a crucial role in disseminating health advice in the absence of formal outreach.

Third, workers’ health decisions are not merely behavioural—they are structured by economic precarity. Choices around rest, hydration, or protective gear are filtered through calculations of lost income, job security, and basic survival. As one interviewee put it, “If I stop working when I feel dizzy, who will pay for dinner?” (INT03, Da Nang). Such statements reveal that adaptation, for precarious workers, is not simply about awareness or willpower—it is a daily negotiation shaped by structural inequalities. These insights illustrate why climate-health governance must account not only for exposure but also for the socio-economic constraints that define the space of possible action.

Such realities challenge dominant assumptions that climate-health adaptation can be driven by behavioural nudges or technological fixes. As Nightingale et al (2024) note, truly just climate solutions must confront the social and political structures that shape risk and response. Co-constructed research helps make these visible, connecting the experiential with the structural, and the quotidian with the historical.

Co-construction is not a decorative gesture—it is a political and methodological commitment to shifting who holds authority over knowledge, and whose realities shape policy. In our research, this meant recognising informal outdoor workers not as data sources but as experts in their own right. Their environmental knowledge—cultivated through daily, embodied interaction with heat, flooding, air quality, and customer flows—is not anecdotal. It is a sophisticated form of localised climate-health expertise.

When a scrap collector adjusts their route based on wind direction, or a food vendor changes their menu during heatwaves, they are not improvising. They are deploying finely tuned strategies shaped by years of sensory learning and social coordination. Such everyday adaptations rarely appear in formal assessments, yet they form the bedrock of resilience within informal economies. When institutional systems fail—as they often do—peer support, mutual care, and improvised infrastructures fill the gap. These are not informal coping strategies; they are critical, yet undervalued, components of adaptive capacity.

Adaptation, however, unfolds under constraint. Chronic illness, limited healthcare, and precarious incomes make it difficult to rest during heatwaves or afford additional drinking water. What policy frameworks often call “behavioural choices” are in reality constrained decisions—calculated trade-offs between health and survival.

This perspective challenges dominant approaches to adaptation that frame vulnerability as a deficit to be corrected through behavioural nudges or technological tools. For informal workers, adaptation is not a discrete outcome—it is a dynamic, everyday process shaped by structural inequality, insecure work, and exclusion from formal systems.

If the climate justice agenda is to be more than rhetorical, it must treat these everyday adaptations not as marginal stories but as central to understanding what effective adaptation looks like. Informal workers are not at the periphery of urban systems—they are the ones who keep them running. Their knowledge is not supplementary. It is foundational.

Too often, participation in climate-health policy is reduced to optics: a workshop, a consultation, or a check-box exercise. As the WHO’s Special Report on Social Participation in Health and Climate makes clear, “social participation is not only a cornerstone of democratic governance but also a critical lever for climate-resilient, low-carbon, and equitable health systems” (WHO, 2025, p. 9). Our work made this real. We engaged institutional actors from the beginning—not as distant policymakers to be briefed, but as reviewers and co-interpreters of worker-generated evidence. This reframing dismantled the hierarchical norms of Vietnamese policy dialogue and created rare spaces for horizontal, deliberative exchange.

Following our fieldwork, we convened three hybrid roundtables bringing together over 200 participants across government, academia, civil society, and worker organisations. These events, covered by local media—a rare move in Vietnam—amplified the visibility and legitimacy of worker knowledge in public discourse around climate and health. They signalled growing institutional willingness to recognise adaptation not only as a technical challenge, but as a social and political one.

This approach is consistent with the Belém Health Action Plan’s call for “equitable, bottom-up approaches” that enable the meaningful participation of the most affected communities in all stages of climate and health policymaking. We didn’t just cite these principles—we put them into practice. By integrating community leadership and institutional engagement throughout, our study offers a replicable model for participatory, locally grounded climate–health governance.

Although our case is grounded in urban Vietnam, the implications stretch across the Global South. In many fast-urbanising regions, informal outdoor workers make up a large share of the urban labour force. They are the backbone of cities—and among the most exposed to heat, pollution, and extreme weather. Yet their voices remain largely absent in climate-health governance.

COP30 offers a critical opportunity to change this. As the WHO report states, “addressing climate change is a commitment to life”—but whose lives are being counted? Co-construction offers a pathway to equity, grounded in shared knowledge, mutual respect, and institutional humility.

If we are serious about climate justice, we must listen to those who adapt daily without support. Informal workers do not need to be empowered—they are already adapting, analysing, and organising. What they need is recognition, redistribution, and responsive policy. Let COP30 be a turning point: from symbolic participation to structural transformation.

This research was supported by the Wellcome Trust [Grant number: 227993/Z/23/Z] as part of our ongoing project ‘the health impacts of climate change on precarious outdoor workers in urban Vietnam’.

Vu, A.N., 2025. Co-constructing climate-health knowledge with informal outdoor workers in urban Vietnam. Commentary. National Centre for Social Research.

Article

Article

Receive a regular update, sent directly to your inbox, with a summary of our current events, research, blogs and comment.

Subscribe